This week we read Pinchas. A lot happens in this portion (like murder), but the part we want to focus on covers a topic that’s near and dear to our hearts, women’s rights. Yes, folks, you heard me right, this week the Torah gets a lil’ feminist.

In this portion, we meet a man named Zelophehad. But don’t get too attached to him, because a few lines after we meet him, he dies. It’s sad, but his death happens to be pretty important. You see, Zelophehad didn’t have any sons, but he did have 5 unmarried daughters (Pride and Prejudice who?). Mahlah, Noa, Holga, Milcah, and Tirza not only have to deal with the death of their father but a whole lot of uncertainty. You see, land is passed down to the male members of the family. If a man doesn’t have any sons, the land would go to his brothers or his parents. Honestly, if it came down to it the land would probably get passed down to that weird 3rd cousin that you only invite to family gatherings because you have to simply because he was a dude.

That’s why there was so much pressure on women to get married. I guess sometimes people married for love, but I would assume it was mostly for women to avoid being homeless and penniless.

Mahlah, Noa, Holga, Milcah, and Tirza didn’t like this, not one bit. So, they did something about it. These women were very smart and they knew that if they wanted to make a change, they would have to go straight to the top. They went to the tent of meeting and in front of all the chieftains and the whole congregation and petitioned Moses and the priest Elazar (Aaron’s son).

The sisters questioned why shouldn’t they get a piece of their father’s land along with his brothers. Their father was a good man and it wouldn’t be fair for his name and legacy to end just because he didn’t have any sons.

Moses then went to G-d and told G-d what happened. G-d tells Moses to give Mahlah, Noa, Holga, Milcah, and Tirza some land along with their uncles. But G-d doesn’t stop there, oh no. G-d then amends the rules of inheritance in the Torah to include women. The rule now states that if a man dies without any sons, then his land will go directly to his daughters. While this is a great victory, this, unfortunately, isn’t the end of the story. In a few portions, we will learn about some high-ranking men from the sister’s tribe who got butthurt over this and went to complain to Moses. They complained that if the sisters married someone from a different tribe, then their land (which is supposed to belong to their tribe) will now be owned by the husband’s tribe. I guess they do make a fair point. So Moses declares that the sisters can only marry within their tribe.

Did Moses technically just promote incest? Yup. However, the Torah is no stranger to incest. Have you read some of the early portions? Anyway, Moses isn’t technically telling them to go marry an immediate relative. Basically, they have to marry a very distant cousin, like a 12th cousin or something. Nevertheless, this is a huge victory. These women found an issue and felt like they weren’t being treated equally, protested, and earned their rights…well, some of them at least. They were the first women in the whole Torah to stand up against this, and yet this doesn’t seem to be a portion that’s talked about a lot. Despite these biblical women earning the right to own land and taking a big step towards equality, it took many, many, many years for women throughout history to earn these same rights.

Just like the Zelophehad’s daughters, women in the United States fought for what they believed they deserved. Almost 100 years ago, on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified. If you don’t know, the 19th Amendment states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” The Women’s Suffrage Movement started in very small groups about 100 years before, in 1820. It picked up speed and became a nationwide movement in 1848. In July of 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY with over 300 people in attendance. Delegates came together to write the Declaration of Sentiments, which mimicked the language of the Declaration of Independence, but instead of saying “all men are created equal”, it stated, “all men and women are created equal”. After this, the movement received a lot of backlash from the press (sound familiar?). However, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott (and later also Susan B. Anthony) pressed on.

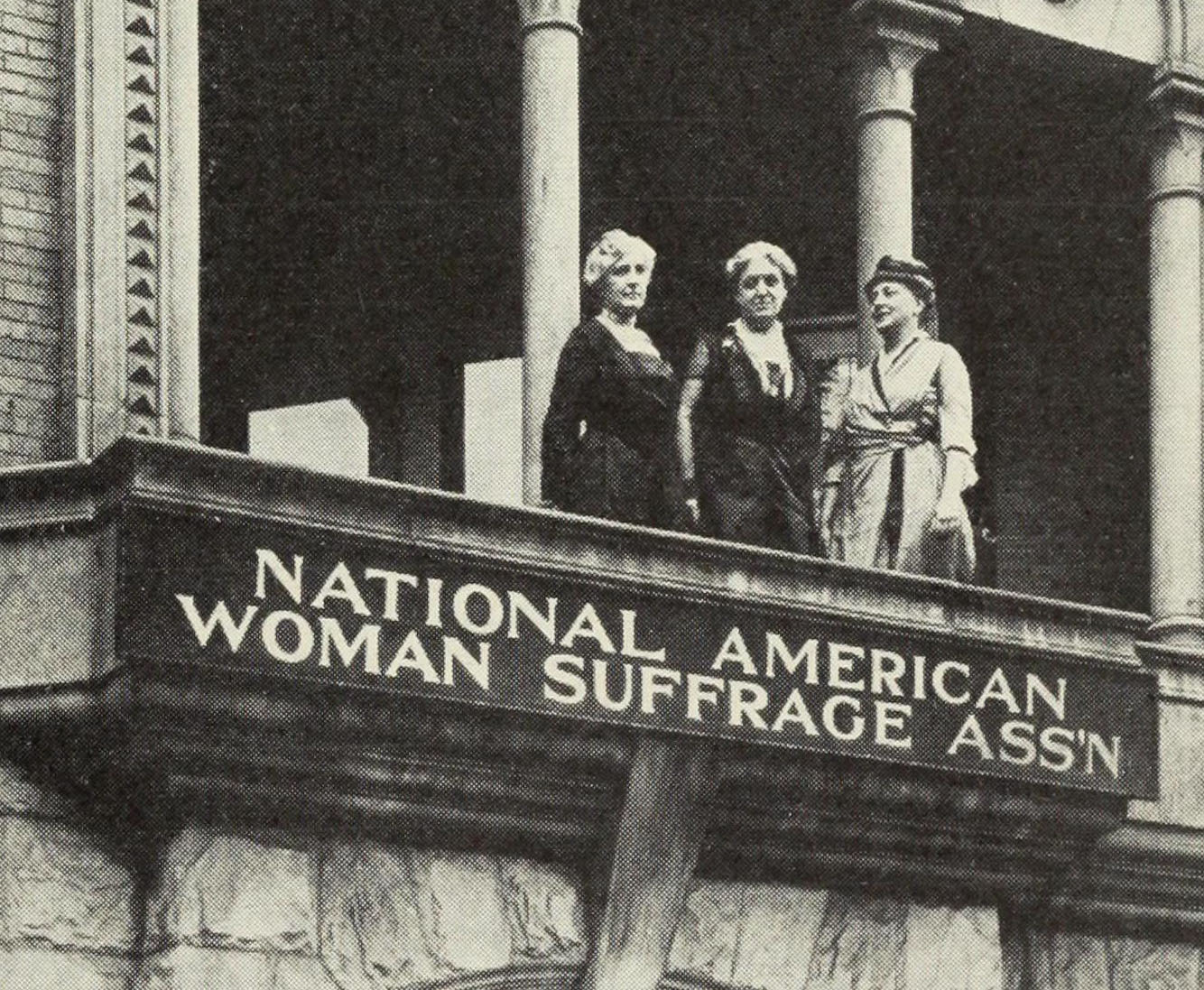

After the war, with differing opinions on the 15th Amendment, two main groups appeared. Later on, in 1890, the two groups merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). This group started petitioning to have individual states change their constitutions to reflect voting rights for women. Slowly but surely, more and more states amended their constitutions to allow women the right to vote. In 1913, on the night before President Wilson’s Inauguration, many women staged a massive “suffrage parade” in the capital. Picketing became a common occurrence in front of the White House. Some women even used militant tactics, which resulted in arrests and jail time. President Wilson showed his support for women’s voting rights in 1918 and the amendment was proposed. It failed in the Senate by two votes. The fight continued until 1919 when it was re-proposed and passed in the Senate by two votes. Slowly but surely states ratified the amendment. It wasn’t until 1920 that it was fully ratified – thanks to Tennessee. It was officially certified on August 26, 1920, and more than 8 million women got to vote for the first time on November 2, 1920.

The movement for women’s voting rights was not perfect. There were some not so subtle moments of discrimination towards women of color. For example, during the women’s suffrage parade, women of color were asked to march at the back of the parade. Totally not cool. Idigenous women’s influence was prevalent at the Seneca Falls Convention. Indigenous women, long before settlement and colonialism, had political voices in their tribes. Their power in their tribes helped inspire the suffragettes. When NAWSA was formed, the individual state groups were given more power to do what they needed to support the movement. Southern states prevented Black women from participating. It was thought that if women’s suffrage was advertised as a way to keep the power in the hands of white people, then the movement would be supported in the South. The movement may have been fighting for women’s rights to vote, but it didn’t always support all women. Even with feminism today, BIPOC (this term stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) women and trans women have been left out. The next steps in the fight for equal and equitable rights for women need to include women in these categories. We need to have intersectional feminism, where we include all women, as opposed to traditional, white only feminism.

It took almost 100 years for this movement to make a difference in law. Pinchas teaches us that women in the Bible stood up for the rights they thought they deserved. What does this teach us? Never to give up when fighting for what we believe in. And make sure, when you’re fighting the good fight, to include the people who need to be included.

Wash your hands, wear a mask, and remember that Black Lives Matter.

Love,

Amanda & Marissa

Sources: